Below is the conclusion from ‘The emerging market for pico-scale solar PV systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: From donor-supported niches toward market-based rural electrification. UNEP DTU Partnership.’

Within the past five years, Sub-Saharan Africa has witnessed incredible growth in the use of pico-scale solar PV products by private consumers. Sales have expanded from less than 100,000 units per year in 2010 to more than 4 million units in 2014, with forecasts expecting further growth in the future. The development has been particularly pronounced in Kenya, Ethiopia and Tanzania, but other countries are also picking up. This report has drawn attention to four decisive factors that, in combination, seem to have coincided to enable the development of the market for pico-scale solar appliances.

First, the generally rising oil prices and derived (petroleum) products, notably diesel and kerosene, have led to an increase in household spending on lighting and electricity. This appears to have created an incentive for the demand for alternative, lowcost sources of lighting and electricity, including solar Pico and SHS systems.

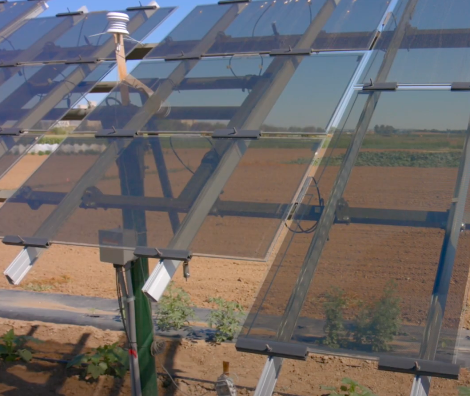

The second factor points at the simultaneous decrease in the cost and increase in the efficiency of core components of solar products, such as solar panels, batteries, BOS components and LED technology. The price/efficiency improvements have meant that pico-solar products are now able to provide the same service as larger systems did previously, at a much lower cost. This has provided a strong impetus for making pico-scale solar appliances affordable and relevant for a larger part of the population, including those with low income.

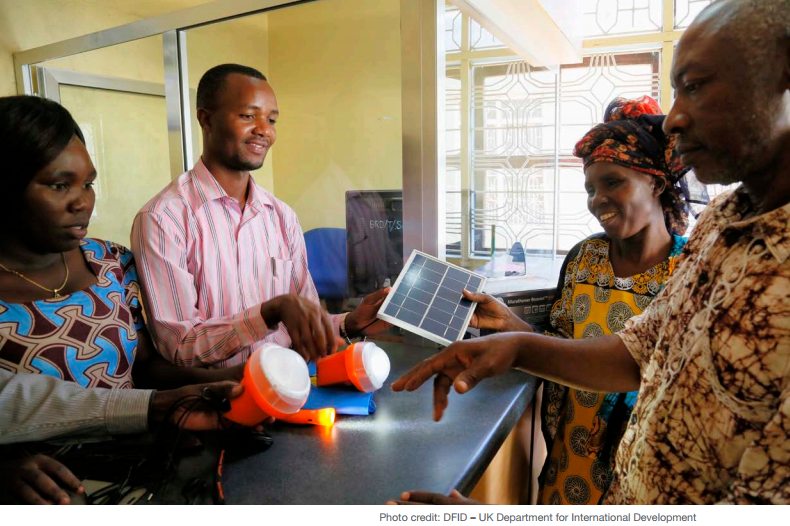

Third, the emergence of new and innovative PAYG business models for payment and delivery of solar PV products is made possible by the widespread use of mobile phones and payment systems, such as the M-PESA system in Kenya. In combination with the introduction of new intelligent metering and monitoring technologies, suppliers of Pico and SHS systems are able to manage the provision and payment of electricity services efficiently. This has enabled entrepreneurs to target even the most remote and low-income groups of society. In turn, the PAYG model offers customers the opportunity to purchase electricity when needed, on a daily basis, thereby avoiding high upfront costs.

The last factor draws attention to the global certification scheme introduced by Lighting Africa, which comprises a system for ensuring the quality of pico-scale solar products. This quality assurance system seems to have provided customers with a greater level of reliability and certainty in the products purchased. Nevertheless, the (large) market for products that are not in compliance with the standard system should not be underestimated, although customers may have less certainty in product quality. While additional research is required to explore these factors and the observed market trends in further detail, some tentative implications may already be drawn at this stage.

As described, the diffusion of small-scale solar in Africa over the last 10 years has gradually moved from being strongly supported by donor organizations to being a fully commercial product sold on market conditions by national and international enterprises to customers outside grid-connected areas. Interestingly, this trend of high-tech green energy solutions diffused by private enterprises can also be identified for the mini-grid sector, addressing people living in villages far from the existing grid. In Kenya, for example, since 2012, four private mini-grid operator start-ups have installed 20-30 mini-grids in the size of 1.4-10 kW, with a few examples of larger systems — 20 and 50 kW.

Two of the companies have received a formal license to operate, and one company has secured financing for establishing a portfolio of another 100 mini-grids (MoEP, 2016). The main difference in individual solutions is that Pico-solutions and SHS provide 12 Volt supply, while mini-grids provide 220 V grid power allowing more universal use of appliances.

Despite obvious regulatory challenges, it is encouraging to see private sector actors providing solutions to energy supply in rural areas, both in terms of pico-lighting devices, larger SHS and, now, also as operators of mini-grids. The private sector interest indicates that the main technological achievements described in this paper –cost reduction of PV, emergence of energy efficient appliances (LED), and mobile phone-based PAYG technology– have created the conditions for viable business models, which may ensure a fast roll out of electricity supply to rural areas. The main drawback in this development path is that leaving rural electrification to the market, and leaving the old principles of equal tariffs in urban and rural areas have social implications benefitting the richest and leaving the poorest groups behind with traditional solutions.

With respect to supporting the poorest individual households outside the reach of grids and mini-grids, experience shows that it is difficult to reach this group with traditional support schemes linked to the product itself (Lee et al., 2016). Support should address the general economic conditions for the poorest groups, enabling them to procure the needed PV devices.

Photo credit: DFID – UK Department for International Development